I GLABRI A RISCHIO DI ESTINZIONE?

Titolo provocatorio ovviamente. Diverso dai precedenti questo nuovo capitolo di Fashion Fil Rouge. Non si racconta né di moda né di storia della moda. Il focus cade invece sull’attitudine da parte dell’uomo di incorniciare il proprio volto con barba e baffi. Una propensione che, in saecula saeculorum, ha conosciuto alti e bassi, ma che, innegabilmente, vive ora convinta stagione di fioritura. Si parte da un postulato, al di là delle alterne fortune di questo vezzo che , in verità, è sempre stato molto più che un vezzo. Da sempre barba e baffi sono considerati manifestazione di mascolinità, “valore” che ne riassume tanti altri: prestanza, avvenenza, abilità guerriera, autorevolezza, potere, saggezza.

Titolo provocatorio ovviamente. Diverso dai precedenti questo nuovo capitolo di Fashion Fil Rouge. Non si racconta né di moda né di storia della moda. Il focus cade invece sull’attitudine da parte dell’uomo di incorniciare il proprio volto con barba e baffi. Una propensione che, in saecula saeculorum, ha conosciuto alti e bassi, ma che, innegabilmente, vive ora convinta stagione di fioritura. Si parte da un postulato, al di là delle alterne fortune di questo vezzo che , in verità, è sempre stato molto più che un vezzo. Da sempre barba e baffi sono considerati manifestazione di mascolinità, “valore” che ne riassume tanti altri: prestanza, avvenenza, abilità guerriera, autorevolezza, potere, saggezza.

Nell’antichità la presenza di barba e baffi sui volti maschili risponde a regole sociali ben codificate. Nell’Atene classica la comparsa della prima peluria è il punto di svolta nei rapporti omoerotici, considerati portanti nel percorso di formazione di ogni uomo. Non appena si manifestano tracce di baffi, il giovane cessa di essere “eromenos”, l’adolescente amato, protetto e istruito alla vita dal maschio adulto, o “erastès”. Più pragmatici, occupati a conquistare una provincia dopo l’altra, i Romani prediligono i visi glabri. Si concedono al massimo barbe corte e curate. E in generale associano la barba a chi non deve imbracciare le armi, in special modo ai saggi, ai filosofi, ai pensatori.

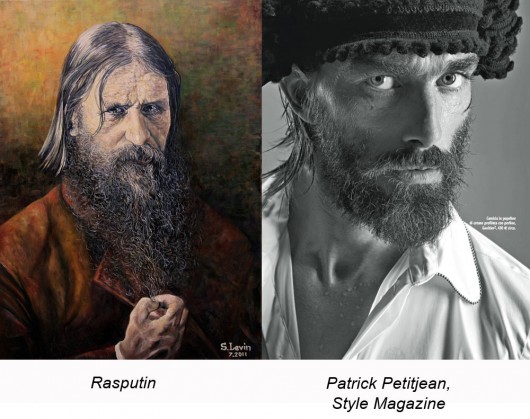

La liaison tra barba e saggezza, ovvero talento, è un leit motiv che percorre la storia di ogni civiltà: da Socrate a Confucio, dai Padri della Chiesa a Karl Marx, da Leonardo da Vinci a Michelangelo, da Lev Tolstoj a Ho Chi Minh. Anche se talora risulta ben labile il confine tra saggezza e fanatismo. Basti pensare a personaggi inquietanti della fatta di Rasputin. Si è detto quanto il mondo romano-latino disdegni barbe e baffi incolti. Ma poi arrivano i barbari, quelli veri. E da allora sin quasi all’Età dei Lumi è un profluvio di peluria. Non si è uomini se non si ha il volto incorniciato da barba e baffi.

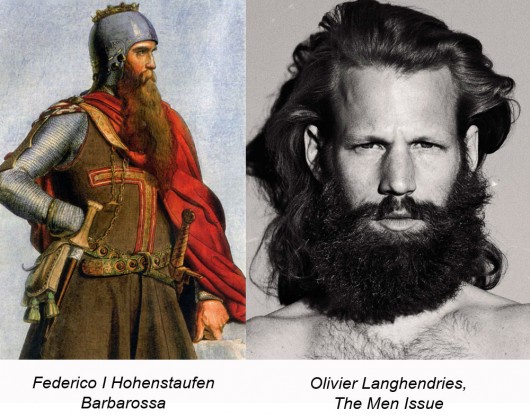

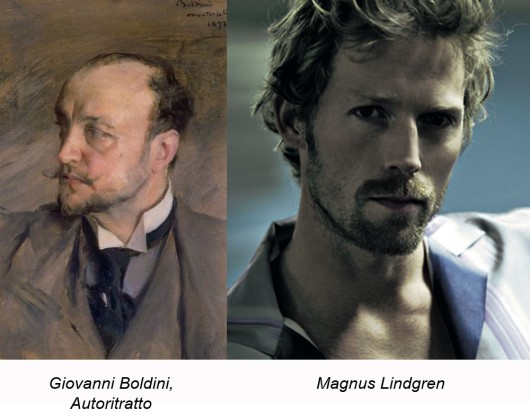

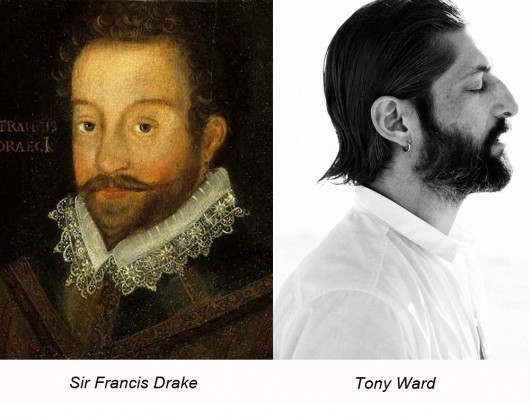

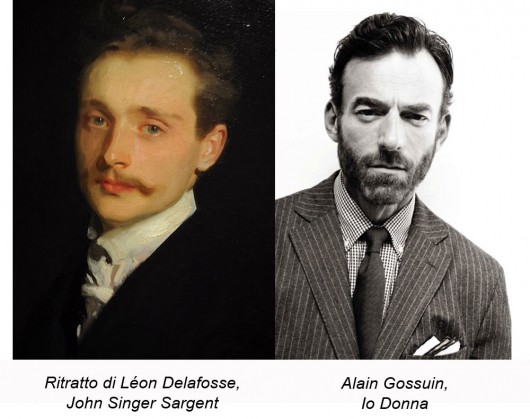

Vale per imperatori e monarchi – Carlo Magno, Federico Barbarossa, Ivan il Terribile, Enrico VIII -, per guerrieri ed avventurieri – i pirati inglesi e i conquistadores spagnoli -, per nobili e borghesi benpensanti – quelli severi, ritratti dai pittori fiamminghi del XVII secolo. Superato l’Illuminismo, era in cui tutti i grandi si propongono glabri – da Federico il Grande a Re Sole, da Voltaire a Kant – quasi a rappresentare l’uomo nuovo, la Restaurazione riporta in auge quantomeno i baffi. Da quelli superbi dei sovrani e governanti – Francesco Giuseppe I, Napoleone III, Vittorio Emanuele II, Bismarck – a quelli più moderati di magnati e capitani d’industria, sino a quelli curatissimi dei dandy ritratti da John Singer Sargent o Giovanni Boldini.

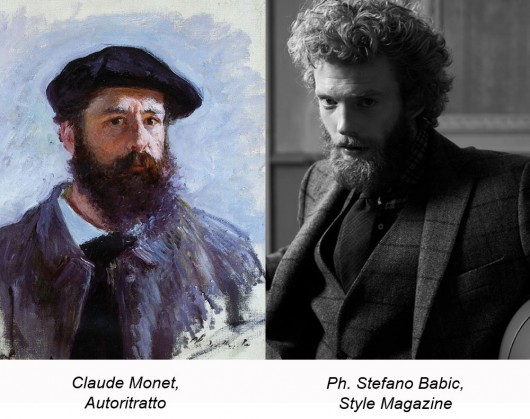

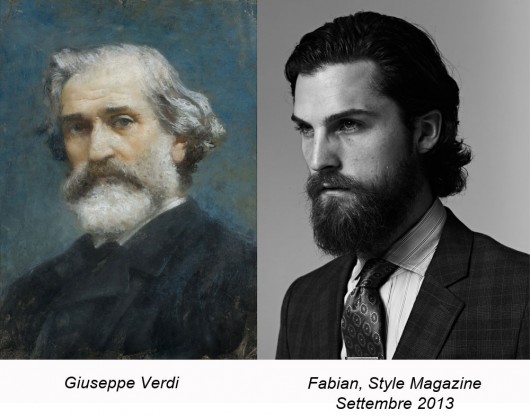

I geni assoluti – dello stampo di Giuseppe Verdi o Claude Monet – possono ancora vantare barbe discretamente fluenti. Al presente, o quasi: la Prima Guerra Mondiale ristabilisce i vantaggi del viso glabro. Chi per quasi cinque anni deve sopravvivere nel fango delle trincee tra fango e pidocchi, non può curarsi anche di barba e baffi. Ed è glabro, in buona parte, il Ventesimo secolo. I miti di Hollywood che optano per i baffi – Clark Gable o William Powell – lo fanno per aggiungere un tocco di malizia al loro fascino. Si ricredono i Sessantottini, in spregio all’ordine borghese.

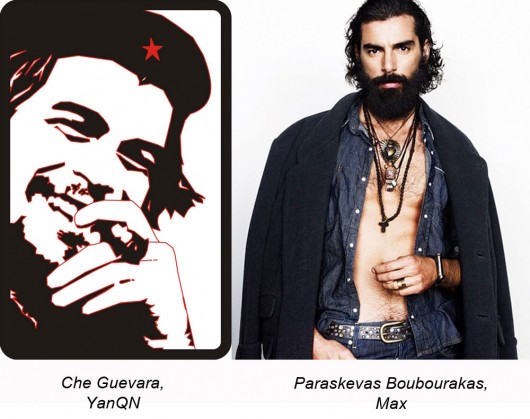

Le loro barbe sono quelle di Fidel Castro e ancor più di Che Guevara. I baffi rimandano all’epopea western alla Wyatt Earp. I “moustache” sono anche eponimo di trasgressione, accompagnano l’emancipazione omosessuale, quantomeno nelle sue espressioni più popolari, come insegnano i Village People. Ed ora? Nessun timore per i glabri. Non corrono alcun rischio d’estinzione. Ma è vero che barbe e baffi popolano oggi le nostre strade di… “not so ordinary guys”…

L’esemplare di maschio dotato di barba e baffi più affascinante di tutta la storia, a parere di chi scrive? E’ Thor Heyerdahl, l’antropologo-biologo-esploratore norvegese che nel 1947 attraversa il Pacifico con il Kon Tiki, “Figlio del Sole”, la sua imbarcazione primordiale costruita e messa in per dimostrare l’ipotesi secondo cui popolazioni Sud-Americane avrebbero colonizzato la Polinesia in epoca pre-colombiana. Alto, slanciato, ieratico come un bramino indiano, impeccabile come Lord Mountbatten, disinvolto e per nulla artefatto nella sua avvenenza (in questo senso gli Scandinavi hanno ben poca dimestichezza con l’artificio), temerario come un Vikingo, acuto e profondo di spirito come uno studioso della scuola alessandrina. Giorgio Re

Risk of extinction for hairless men? A provocative title. This new chapter of Fashion Fil Rouge is different from the others. We don’t talk about fashion or history of fashion. But the focus is on men’s flair for beard and mustache. An inclination that followed, through centuries, higs and lows, but now lives, undeniably, a second youth. Beard and mustache have always been an expression of masculinity, a “value” that includes a lot of others: thew, attractiveness, courage, authority, power, wisdom. In ancient times beard and mustache on men’s faces were the result of precise social rules. In classical Athens the growth of the first downy hairs was the turning point of homoerotic relations, considered essential in every man’s education. As soon as he had a trace of mustache, the young man ceased to be a “eromenos”, the beloved adolescent, protected and educated on life by the adult male, or “erastès”. More down to earth, involved in conquering territory after territory, the Romans preferred hairless faces. They allowed themselves just a short and trim beard. And, on the whole, they connected beards to wisemans, philosophers, intellectuals. The link between beard and wisdom, is a leitmotif that goes through every culture’s history: from Socrates to Confucius, from the Church Fathers to Karl Marx, from Leonardo da Vinci to Michelangelo, from Lev Tolstoj to Ho Chi Minh. Even if sometimes there’s a blurred line between wisdom and zealotry. Just think about Rasputin, for example. We’ve already talked about the rejection of Romans for unkempt beards. But then came the Barbarians. And from then to the Enlightenment age it had been a profusion of hair. You weren’t a man if you hadn’t your face framed by beard and mustache. This is for kings and emperors – Charlemagne, Frederick Barbarossa (