SHAKESPEARE IN STYLE

Con Cristopher Marlowe, William Shakespeare è il testimone più acuto ed insieme il più raffinato cantore dell’ascesa dell’Inghilterra. Compiuta la riforma anglicana, ridimensionato con forza poderosa il pericolo spagnolo, realizzata un’alleanza – nel complesso solida – tra monarchia, aristocrazia e classe borghese-mercantile, a cavallo tra l’era di Enrico VIII e quella di Elisabetta I, nel regno oltre Manica inizia “The Golden Age”.

L’Inghilterra entra a pieno titolo nel novero delle grandi potenze internazionali. La dinastia Tudor porta il Paese a confrontarsi alla pari con i nemici di sempre, Spagna e Francia, ma anche con il Portogallo, l’Impero germanico, l’Impero ottomano, gli Stati italiani, in breve con il G8 di allora. E’ chiaro che l’accresciuto prestigio del regno offre terreno fertile al boom delle arti. Tra le varie figure in campo, quella di Shakespeare è quella che che sa esprimere al meglio l’apoteosi appena raggiunta.

Il figlio del guantaio e conciatore di Stratford Upon Avon, destreggiandosi con talento fra tragedia e commedia, è l’uomo giusto che fa la cosa giusta nel momento giusto: non solo lancia l’Inghilterra nell’Olimpo delle nazioni con una produzione artistica di valore universale, ma anche e soprattutto “dipinge” un grande passato per la nuova grande potenza. Senza dubbio interpretandolo, adeguandolo al gusto dell’epoca – nonché al bisogno di grandeur del neonato Impero -, accostandolo al passato di altre realtà, la Danimarca di Amleto ed in particolare la Roma antica di Giulio Cesare, di Coriolano, di Marco Antonio, di Tito Andronico.

Sia chiaro: nelle sue opere, il passato remoto o prossimo dell’Inghilterra non è edulcorato tout court. Calibrandoli in giusta dose, Shakespeare mette in scena non poche virtù ed altrettanti vizi dello status ante quo: coraggio guerriero, fierezza, spirito indomito, ma anche congiure, intrighi, persino follia. Vale per “Re Lear”, “Macbeth”, “Enrico IV”, “Riccardo II” e così via. Senza perdere di vista, come si è detto, altre dimensioni, anche a lui contemporanee, come nel caso di “Otello” o de “Il mercante di Venezia”.

Riservando tuttavia all’ Italia – secondo un luogo comune ampiamente diffuso e persistente nei secoli – il ruolo di scenario perfetto per situazioni idillico-arcadiche – nel “Sogno di una notte di mezza estate” – o comunque per l’amore, felice o infelice, ma in ogni caso infarcito di equivoci, da “Molto rumore per nulla” a “Romeo e Giulietta”. La rappresentazione di questo mondo così composito ha nel teatro shakespeariano il suo luogo deputato.

Ciò fa di questa esperienza qualcosa di democratico ante-litteram, anche per quanto riguarda lo stile, il modo di vestire: a differenza di quanto accade nella Francia delle tragedie di Corneille o di Racine, a Londra anche il popolino, insieme alla nobiltà e alla stessa Corona, trepida per la sorte di Giulietta o di Desdemona e ride delle baruffe delle “Allegre comari di Windsor” o della “Bisbetica domata”.

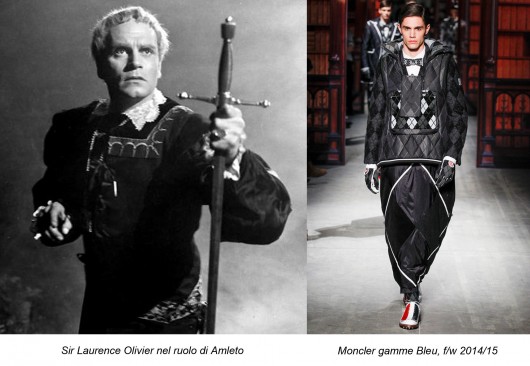

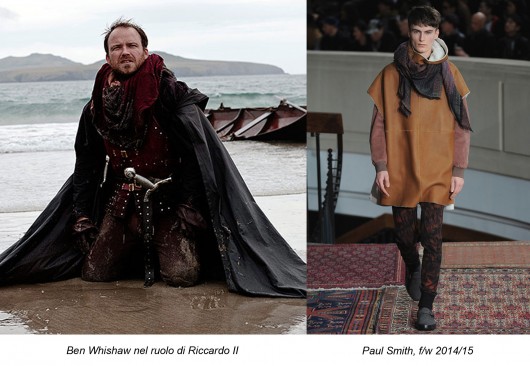

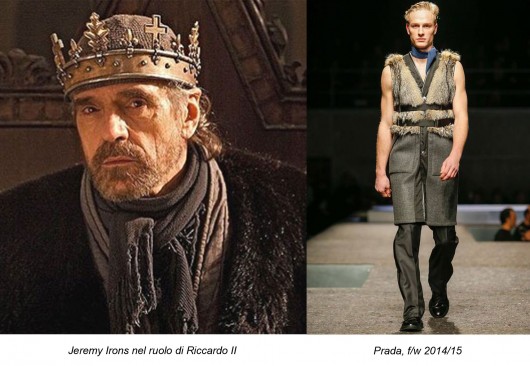

Al contempo osserva cosa indossano eroi ed eroine. Il palcoscenico è in qualche modo anche passerella, luogo in cui non solo si racconta una storia, ma anche si propone uno stile che fa presa sul pubblico. Secondo una dinamica bidirezionale: la moda inglese dell’epoca – che guarda a Parigi o alle corti italiane – sale al palcoscenico e dal palcoscenico discendono ispirazioni che condizionano il gusto, soprattutto a corte o nei circoli nobiliari. In un’epoca in cui la concezione filologica del costume di scena è ancora di là da venire, Amleto, Giulio Cesare oppure Otello vestono non tanto diversamente dal Duca di Buckingham, da Sir Francis Drake, dal conte di Leicester, il favorito della Regina Vergine.

Allo stesso tempo, le pellicce barbare alla Re Lear, le armature alla Enrico IV si rispecchiano nelle pellicce e nelle armature dei nobili britannici. Non meno dei mantelli tartan alla Macbeth, per quanto viscerale sia la rivalità tra Inghilterra e Scozia. Evidentemente anche allora la moda misconosceva le frontiere spazio-temporali. Cosa che nel tempo non è affatto mutata. Conclusione? Lo stile ed i richiami “Cool Britannia” a cui ben pochi stilisti di oggi sanno resistere deve parecchio a quella primordiale passerella che è stata il teatro shakespeariano. God save the style. Giorgio Re

Shakespeare in Style. Together with Cristopher Marlowe, William Shakespeare is the smartest and the most refined witness of the rise to power of England. After the Anglican reform, with a decrease of the spanish danger and a strong alliance among monarchy, aristocracy and middle-class, in the period between Henry VIII and Elizabeth I starts “the Golden Age”. England is part, with full rights, of the great international authorities. The Tudor dynasty leads the nation to be an equal of Spain, France (the enemies), Portugal, the germanic empire, the ottoman empire, the italian States, in brief the G8 of those years. The increased prestige of the reign offers consequently a rich soil for arts’ boom. And Shakespeare is the figure that knows best how to express the just reached apotheosis. The son of a glover and tanner from Stratford Upon Avon, coping with tragedy and comedy, is the right man that does the right thing at the right moment: he gives to England an artistic production with universal importance, but above all he “depicts” a great past for the new great nation. Surely interpreting it, adapting it to that era’s taste – and of course to the needs of greatness of the newborn Empire -, comparing it with other nations’ past, Hamlet’s Denmark and especially Julius Caesar’s, Coriolanus’, Mark Antony’s, Titus Andronicus’ ancient Rome. To be clear: in his poems, England’s remote or recent past is not totally sugarcoated. With a right balance, Shakespeare puts up not many virtues, and vices, of the ante-quo status: bravery, dignity, energy, but even conspiracies, tricks, madness. Think about, for exaple, “King Lear”, “Macbeth”, “Henry IV”, “Richard II”. Without losing sight of, as told before, other dimensions, for exaple “Othello” or “The merchant of Venice”. However saving for Italy – pursuant to a very popular and persistent commonplace – the role of the perfect scenery for idyllic-pastoral situations – in “Midsummer night’s dream” – or anyway for love stories, happy or troubled, but always full of misunderstandings, from “Much Ado about Nothing” to “Romeo and Juliet”. The representation of this heterogeneous world finds its perfect place in the shakespearean theatre. This is a kind of ante-litteram democratic experience, even in terms of style, clothing: unlike what happens in France in tragedies of Corneille or Racine, in London even the common people, together with the aristocracy and the Crown itself, worry for Juliet’s or Desdemona’s fate and laugh at the quarrels of “The Merry Wives of Windsor” or of “The Taming of the Shrew”. At the same time they look at what heroes and heroines wear. The stage is a kind of catwalk, a place where a story is told, but also where a style, captivating for the audience, is suggested. Following a bidirectional dynamics: english fashion of that era – inspired by Paris or the italian courts – goes on the stage and from the stage come inspirations that influence the trends, mainly in courts or aristocratic circles. Too early for a philological idea of the stage costume, Hamlet, Julius Caesar or Othello dress not so differently from the Duke of Buckingham, from Sir Francis Drake, from the Count of Leicester, the favourite of the Virgin Queen. At the same time, the barbarian furs of King Lear, the armours of Henry IV replicate those worn by british aristocrats. Not less than the tartan capes of Macbeth, no matter how innate was the rivalry between England and Scotland. Fashion clearly ignored even then the spatio-temporal frontiers. At the end? “Cool Britannia” style and reminds, which today are irresistible for many designers, owe a lot to that primordial catwalk that the shakespearian theatre was. God save the style. Giorgio Re